Dante's Inferno: Canto XII

Divine Comedy Series- Summary of Inferno, Canto 12. Fixing potholes is free in Hell, but the circle is mismanaged by Centaurs and a Minotaur!

DIVINE COMEDY SERIES

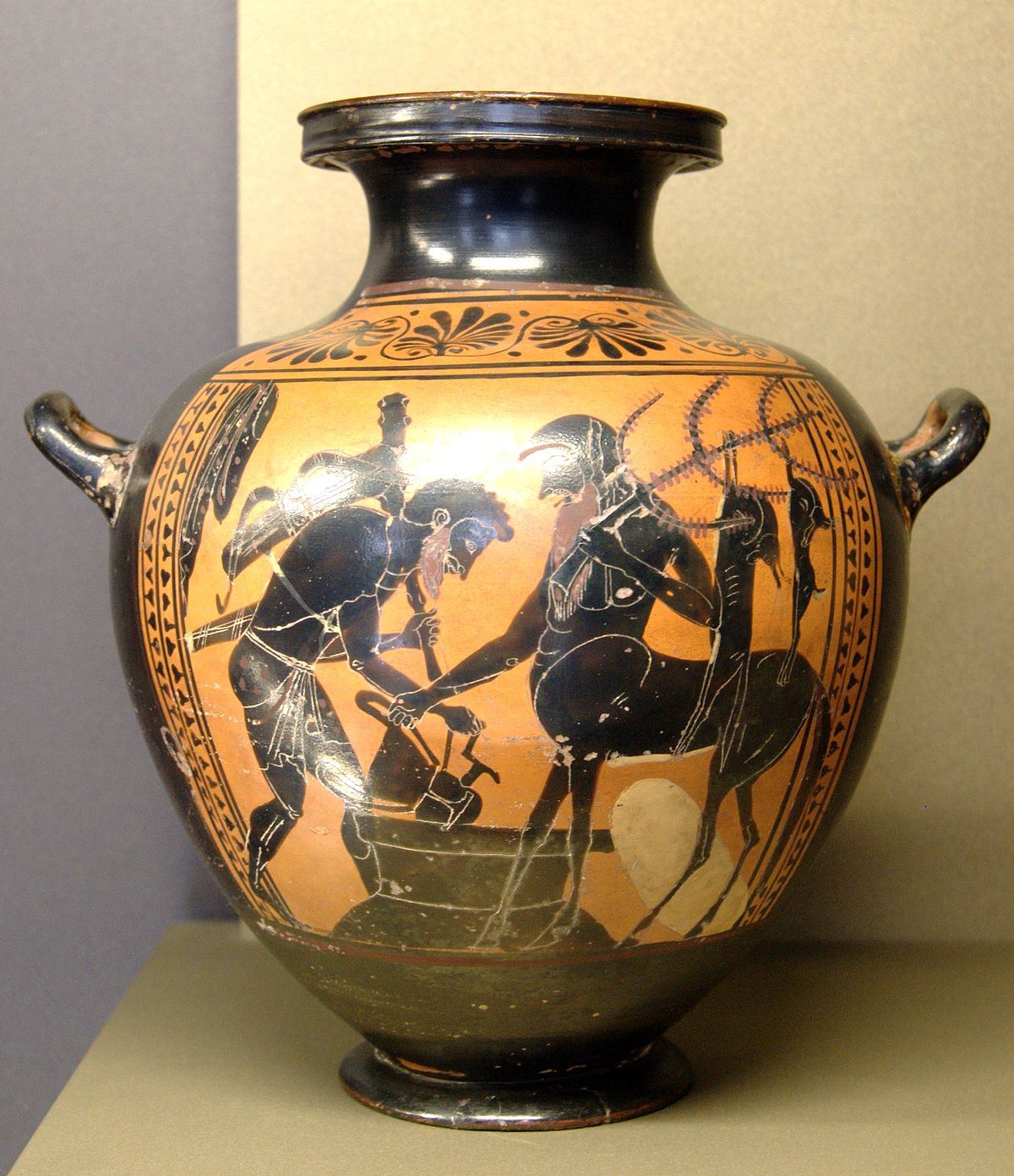

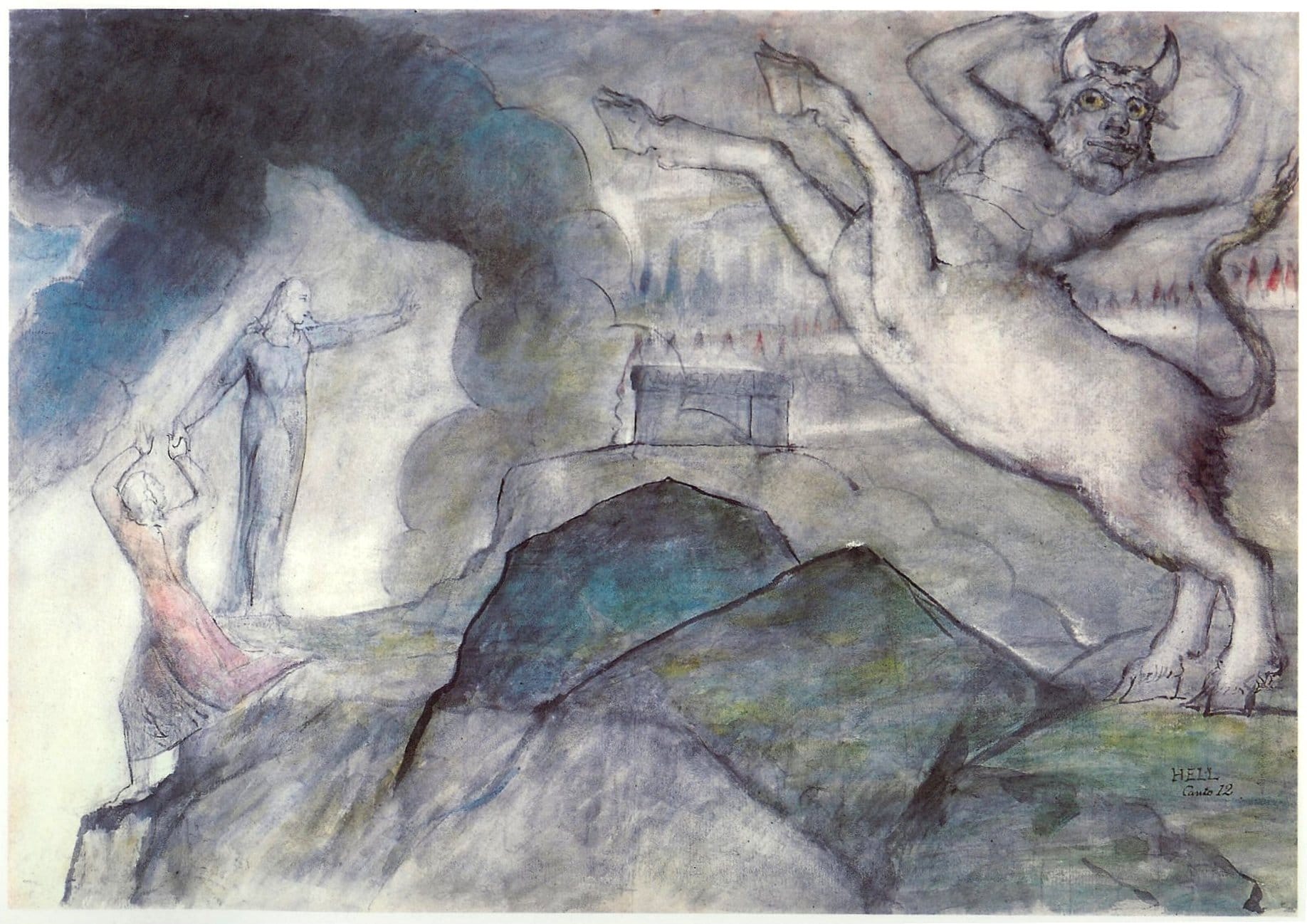

After the discursive (and maybe a bit boring) interlude of canto 11, the twelfth canto returns to the realm of imagination, showing us the Minotaur, centaurs and those who are guilty of violence against the person or possession of others.

Remember where we were? Our two poets have finished describing us the 7th circle, which is divided into 3 sections and we'll now approach the first one (how nice 😄)

Farming encounters

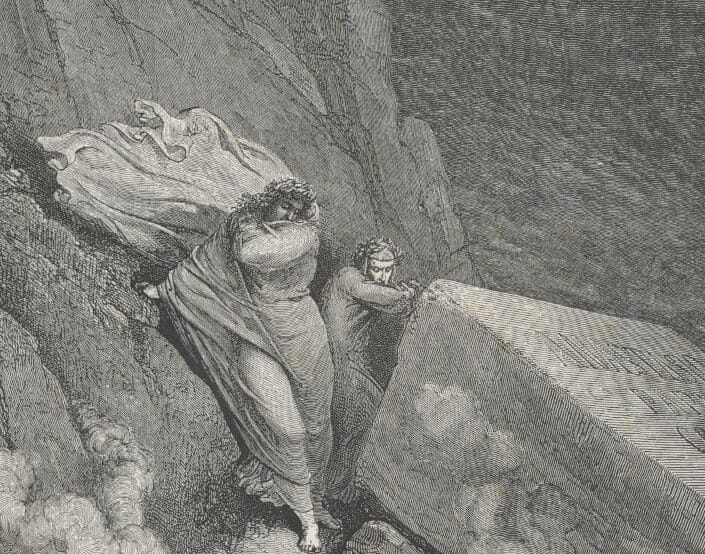

The point where Dante and Virgil descend from the VI to the VII Circle is impervious, as the descent is similar to the landslide that hit the bed of the Adige.

The place that we had reached for our descent

along the bank was alpine; what reclined

upon that bank would, too, repel all eyes.

Line 1–3 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 12)

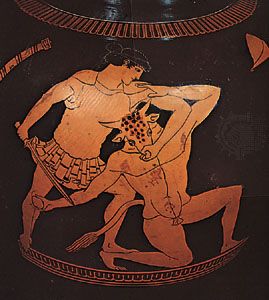

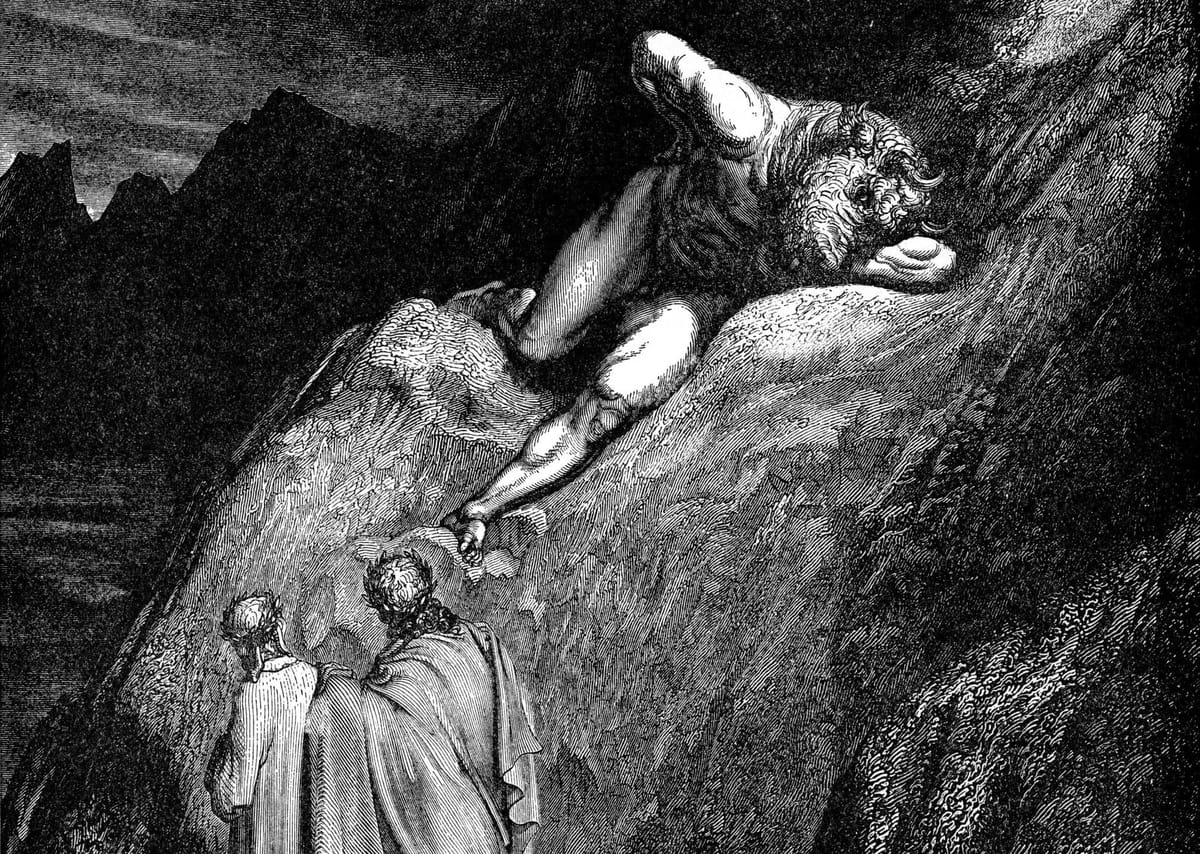

On the upper end of this ruin is the Minotaur, who as soon as he sees the two poets, bites himself with anger - Alighieri refers to him in quite an unusual way

there lay outstretched the infamy of Crete

Line 12 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 12)

Have you noticed how I wrote "the Minotaur" and not "a Minotaur"?

Like the Latin poet Ovid, Dante using abstract words seems to evade to name such a monster. Indeed it is the legendary creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull; born from Pasiphae, wife of the king Minos (king of Crete), and from a bull from which she fell in love (gotta love Greek mythology).

Post-traumatic Stress

Virgil shouts at him that none of them is Theseus, the hero who killed the monster on Earth, and Dante is not here on Ariadne's instructions but to see the punishments of the damned.

Be off, you beast; this man who comes has not

been tutored by your sister; all he wants

in coming here is to observe your torments

Line 19–21 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 12)

The creature goes away hopping, like a bull that has received a mortal blow, and the two poets take advantage of this to move away and climb down the steep rock.

Origin of the landslides in the Inferno

Virgil senses that Dante is wondering what is the origin of the ruins and landslides where the Minotaur was guarding, and explains that the first time he passed by there (shortly after his death, therefore before the birth of Christ) it was not there yet.

However, a short time before the resurrected Christ took the souls of the biblical patriarchs from Limbo (see canto 4), the entire infernal valley trembled in a very strong earthquake and it was this that caused the collapse.

Virgil then invites Dante to look in front of him, where there's a river of blood in which the violents are immersed.

A new river and a possible prequel?

Virgil references the “other time” he came this way, is to reassure the pilgrim that he knows what he is doing.

However, any reference to Virgilio’s first trip to lower Hell only serves to cast a shadow over our beloved guide, since it reminds us that he once undertook this same journey under the aegis of a very different power from the one that sends him now (see canto Inferno Canto 9).

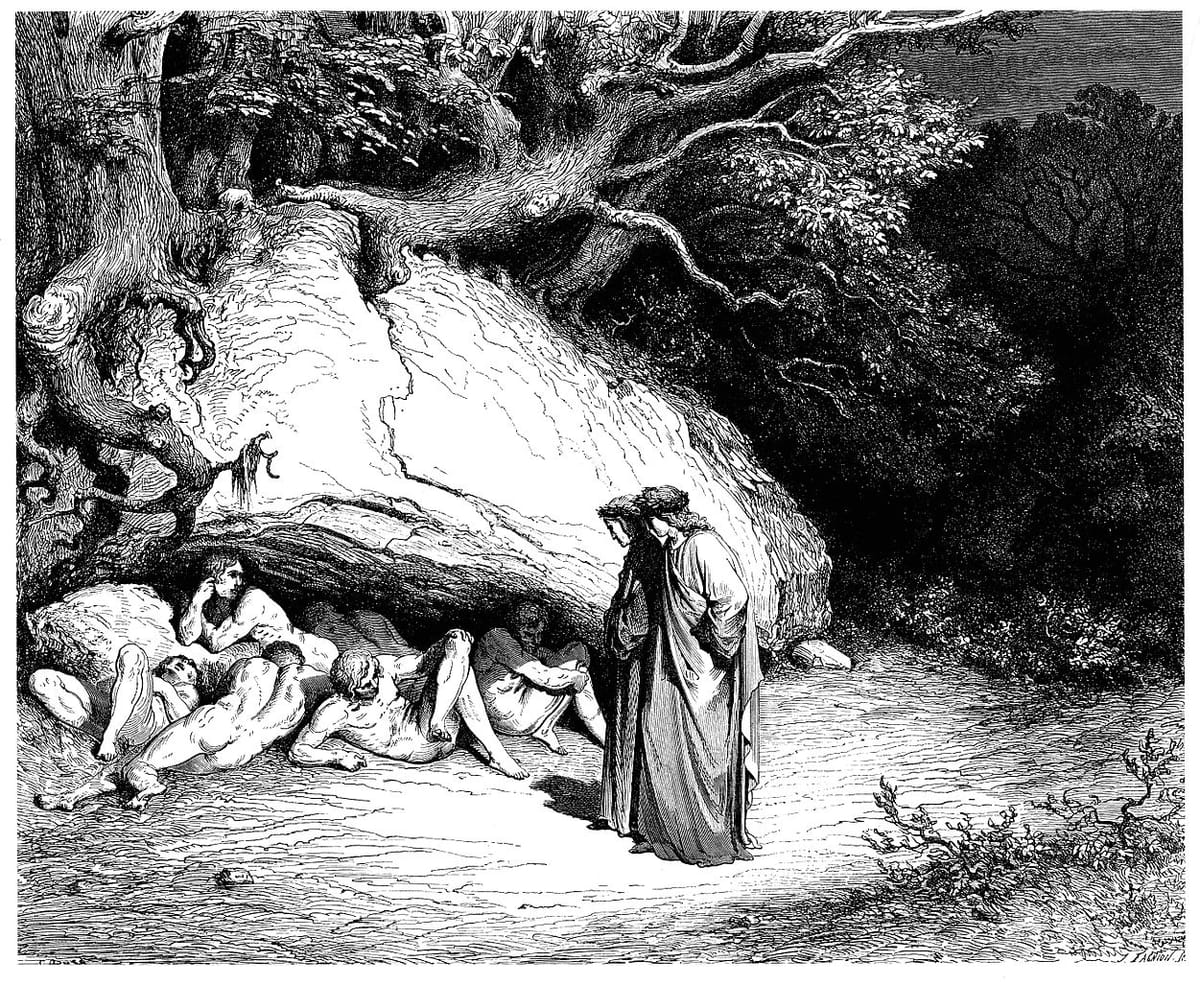

Phlegethon and Centaurs

But fix your eyes below, upon the valley,

for now we near the stream of blood, where those

who injure others violently, boil.

Line 46–48 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 12)

The travellers see what lies before them in the first ring of the circle of violence. As explained in Inferno 11, the first ring of the seventh circle is devoted to: punishing those who committed violence against their neighbour, in the neighbour’s person and her/his possession.

These are: Murderers, Raiders and Tyrants

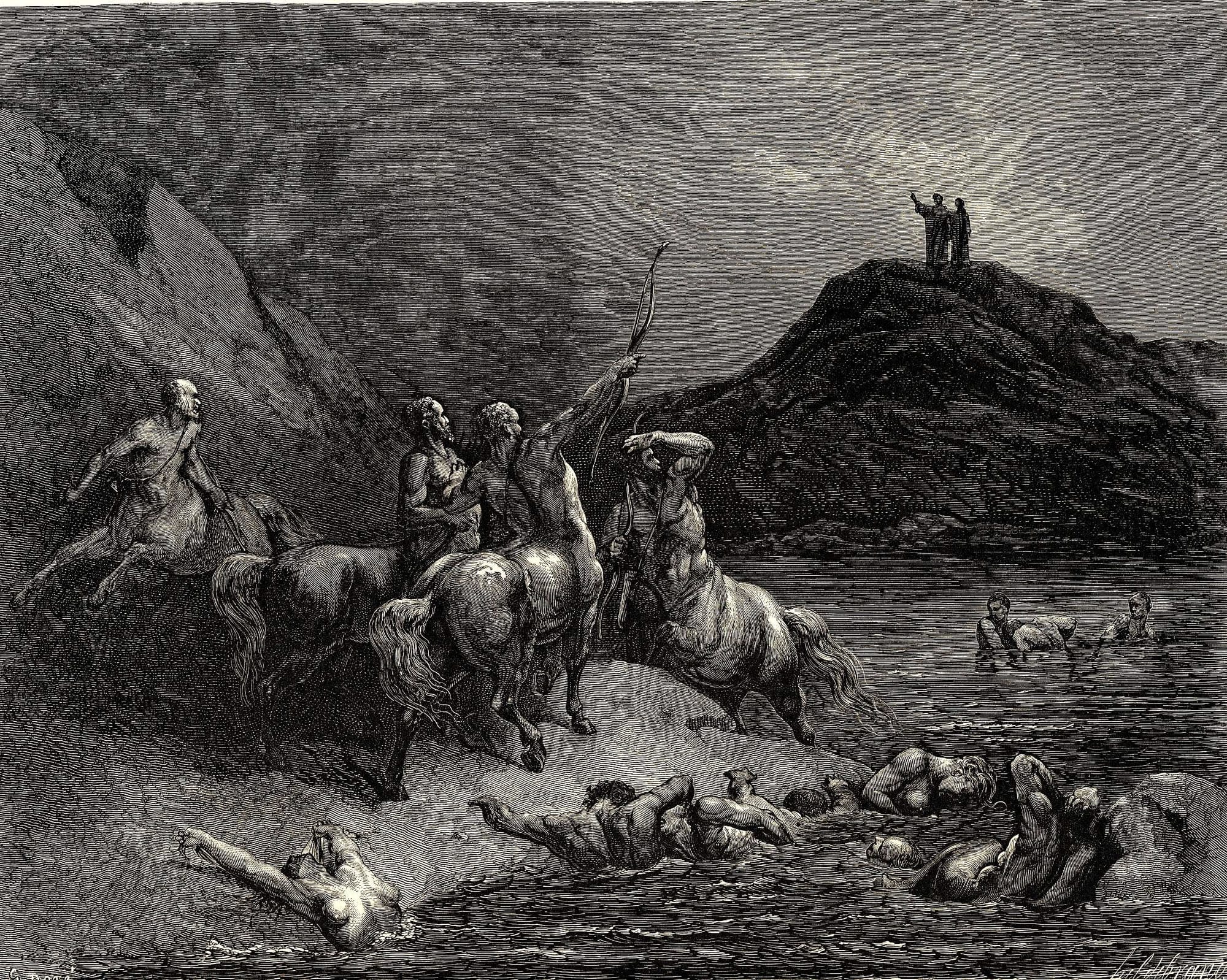

The poet tells us of a large pit in the shape of a semicircle, in which flows a river of boiling blood, the Phlegethon (I would expect such a difficult spelling from such a river!), and between the wall of the Circle and the river run some Centaurs, armed with bows and arrows.

Meeting with Chiron

One of the creatures asks from afar what the sin of the travellers is, threatening them with the bow.

I wonder, what's the point of threatening in a place where you a damned anyway?

Virgil answers that he will explain everything to their leader, Chiron, and then tells Dante that the centaur who spoke is Nessus, who died because of Deianira, while the one in the centre is Chiron, who raised Achilles; the other is Pholus, one of the most violent.

There are thousands of them around the river, with the task of shooting with arrows the damned who come out too much from the boiling blood.

The two poets approach Chiron, who indicates to his companions that Dante is still alive.

When he’d uncovered his enormous mouth,

he said to his companions: “Have you noticed

how he who walks behind moves what he touches?

Line 79–81 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 12)

Virgil then asks Chiron to assign one of his companions to carry Dante on his back and make him cross the Phlegethon, since Dante has a physical body.

Chiron delegates the centaur Nessus to guide the travellers to the ford and to carry the pilgrim over the river. This is the first occasion in which one of the infernal guardians is assigned to serve as a local guide and assistant for the travellers.

The VIPs of the circle

Nessus obeys and escorts the two poets along the river, where the damned shout because of the pain. The river level gradually decreases, until it rejoins the opposite point where it is deeper and where tyrants are punished.

Who were they?

Right, let's proceed with order, I will be brief with the famous ones as you can find them everywhere, but I will spend a bit more time with the lesser-known ones.

At the deepest point, we have the tyrants who plunged their hands in blood and plundering (covered up to the eyebrows)

Alexander: It is agreed that this is Alexander the Great, the famous Macedonian emperor of Hellenistic times

Dionysius: Probably lesser known, was a tyrant in Sicily. He was a bit hated, but made Syracuse the most powerful Greek city west of mainland Greece. All ancient historians speak of him as an example of savagery and ferocity.

Ezzelino III: an Italian feudal lord, a close ally of the emperor Frederick II and ruled Verona, Vicenza and Padua for almost two decades (1232–59). The Guelphs recall him as an author of cruel murders, and a legend called him "Son of Satan".

Obizzo II d'Este: Lifelong ruler of Ferrara (1264), Lord of Modena in 1288 and of Reggio in 1289. His rule marked the end of the communal period in Ferrara and the beginning of the Lordship (or Tiranny), which lasted until the 17th century.

In the middle, covered up to the throat we have the murderers and we only have the pleasure of meeting Guy de Montfort, Count of Nola (a special name as this one comes from England).

He murdered a cousin of King Edward I in 1271 in a church at Viterbo, where the cardinals had gathered to elect the pope.

At the shallowest point, we have the Raiders (aka thieves)

Attila: Attila was the king of the Huns from 434 to 453. He was one of the greatest of the barbarian rulers who assailed the Roman Empire, invading the southern Balkan provinces and Greece and then Gaul and Italy. Following a legend mentioned in Canto 13, he reduced Florence to ashes.

Pyrrhus: (born 319 bce—died 272, Argos, Argolis) was the king of Hellenistic Epirus whose costly military successes against Macedonia and Rome gave rise to the phrase “Pyrrhic victory.”

Sextus Pompeius: (Born 67 BC) The younger son of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, he became a pirate, raiding across the whole Italy. Dante discovered this from Lucan, but also from Orosius.

Rinier Pazzo (mad) and Rinier da Corneto: Two notorious brigands in Florence at the time of Dante Alighieri.

After reaching the other shore, the centaur returns to where he came from, thus ending the canto.

Conclusion

In this Canto we can sense a strong aversion from Dante towards tyrants.

Implicit is Alighieri's criticism against those political regimes that resulted in the oppression of the people (also present in other passages of the poem), and which here identifies examples taken from various historical eras.

the tyrants of poet's time are however more numerous, as the examples of thieves and murderers.

Can you blame him? We can surely recall more tyrants in recent times than the ones of the past if we have to think on our feet.

Hope you enjoyed this Canto XII (12) analysis, I’ve been reading it after a pleasant day in good company with my friend Rupesh, while sorting out a collection of post stamps in London.

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact me via email or the comment section below.

As usual, find some useful links below and don’t forget to comment and subscribe!

Useful Links