Dante's Inferno: Canto XI

Divine Comedy Series- Summary of Inferno, Canto 11. Does stench stop you from doing things or motivate you to find a Pope?

DIVINE COMEDY SERIES

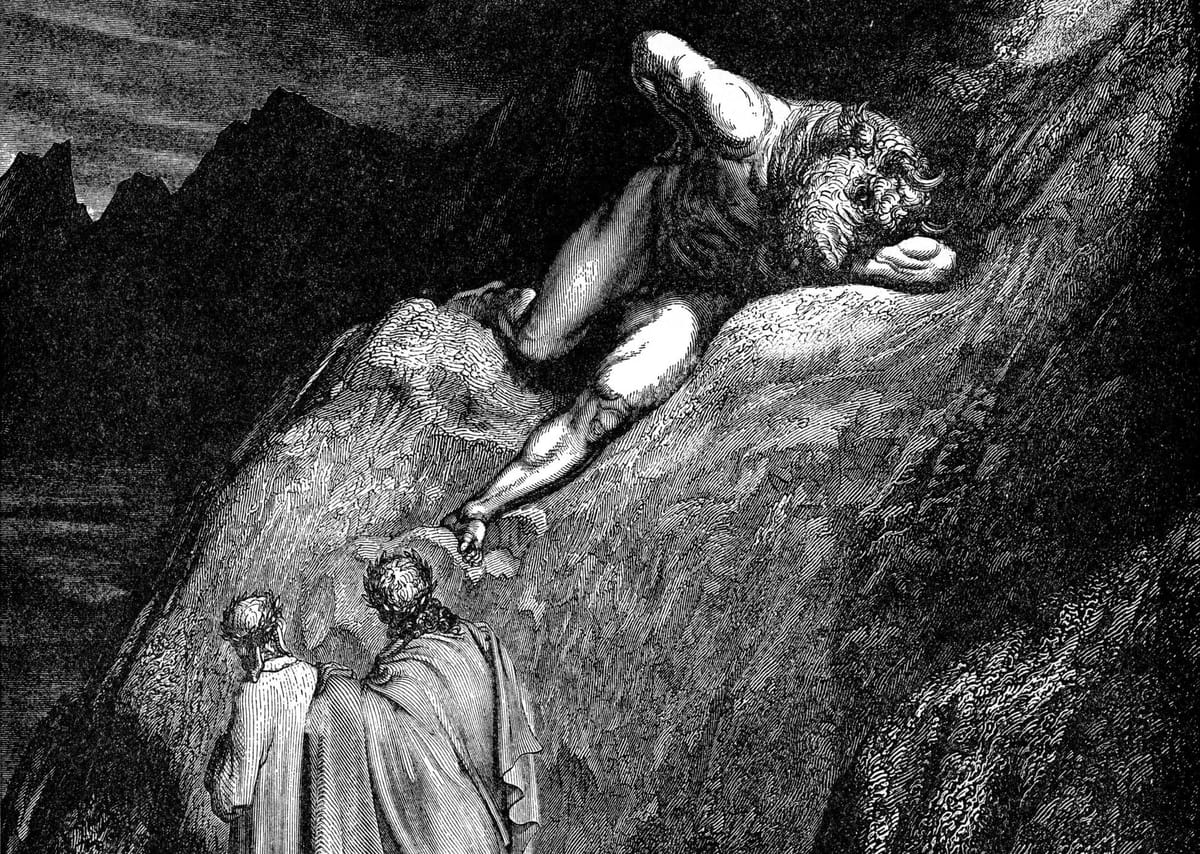

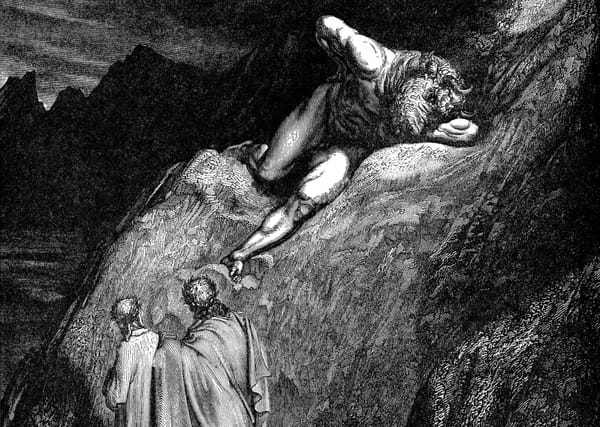

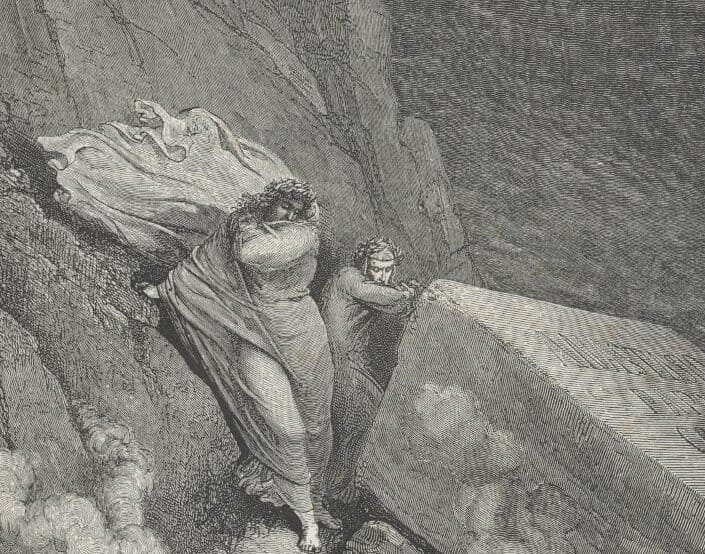

Now passed the lovely encounters with the previous gentlemen, the two poets are still in the city of Dis, where heretics are punished. Dante and Virgil await on the bank of the VII Circle, but now have to stop because of an unusual problem (probably not bowel movements).

It is the night of Saturday, April 9 (or March 26) of 1300, around four in the morning.

A Pope and a strong smell

And here, because of the outrageous stench

thrown up in excess by that deep abyss,

we drew back till we were behind the lid

of a great tomb, on which I made out this,

inscribed: “I hold Pope Anastasius,

enticed to leave the true path by Photinus.”

Line 4–9 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 11)

Our protagonists find themselves on the edge of the 7th circle where they find something quite odd, a tomb (well, we've already seen so many, no?).

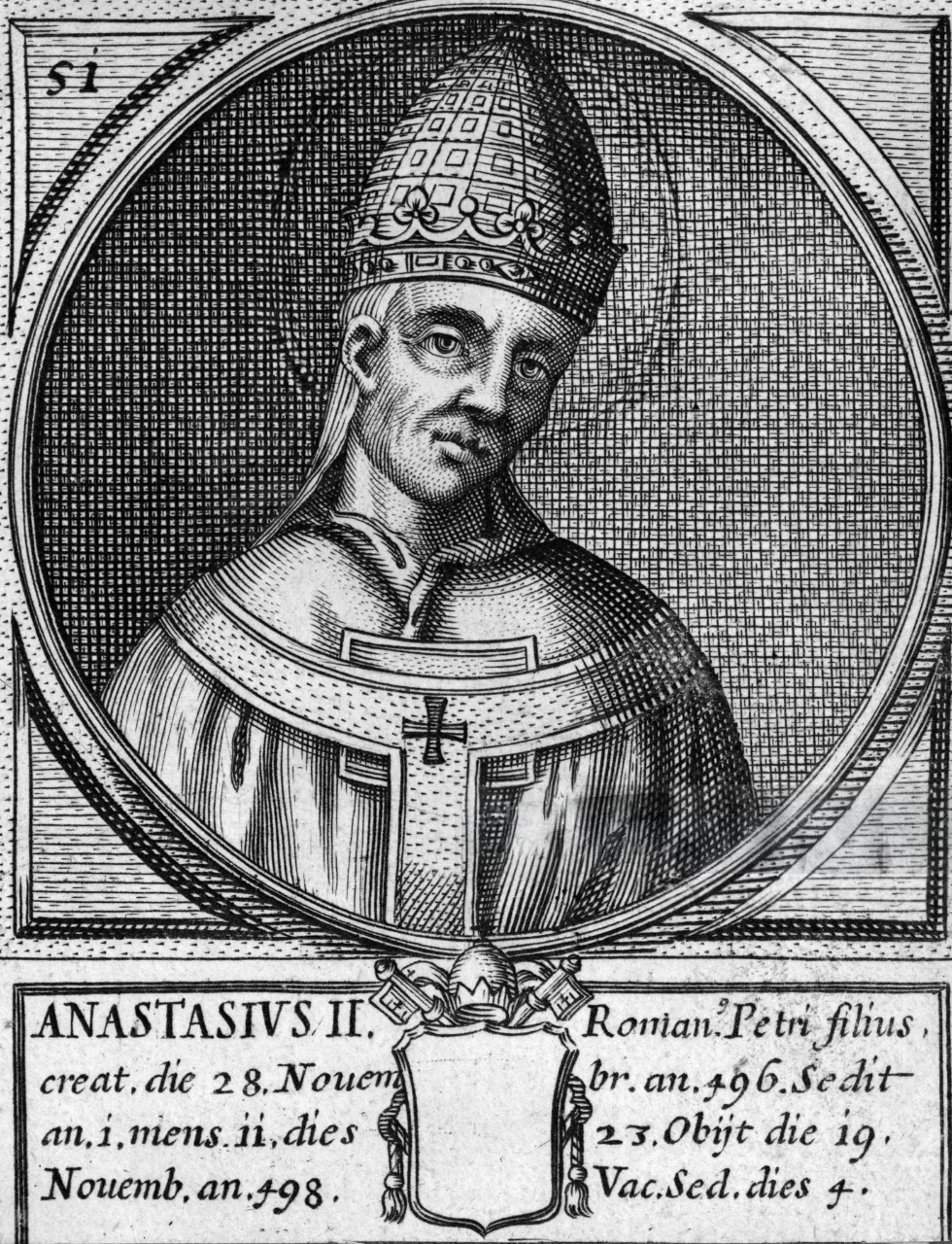

Indeed we have, but this one is the tomb of Pope Anastasius II.

Anastasius (the Second), was a Roman cleric who assumed the papacy in 496 and held the office until his death in 498 (quite short for a pope). His pontificate was a tumultuous period marked by significant ecclesiastical and political tensions.

He is primarily remembered for his attempts to reconcile the Roman Church with the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which had been estranged since the Acacian Schism. His conciliatory approach, however, proved controversial, particularly among those who favoured a more assertive stance against the Eastern Church.

Photinus of Thessalonika, Deacon of Thessalonica, was a friend of Acacius, whose doctrine he shared (see Acacian schism).

In 498 he was sent to Rome by Bishop Andrew of Thessalonica to start a negotiation of reconciliation between the Eastern Churches and the Roman Church.

Pope Anastasius II (our guy) welcomed Photinus kindly, starting a dialogue that upset the high ranks of the Roman clergy. According to a tradition based on a probably corrupted passage of the Liber Pontificalis, Anastasius II (who died on November 17, 498) was stopped by divine will.

Dante, who accepts this tradition, places Anastasius II among the heretics (Inferno XI) and says he was led astray by Photinus.

Got a headache yet? Don't worry, I had to read this 3 times to understand it!

Why does Dante mentions a Pope?

After the group of Ghibellines mentioned in Canto 10, the naming of a Pope here probably means that heresy is not a fact specific to a political party (in this case anti-papal), but can also affect the very top of the church.

Oh yes, if it affects the church, trust me it got to the Tories too (British sarcasm here).

Therefore Dante does not randomly choose this name, as usual, he wants to distinguish the "Church office", the hierarchy itself, from the guarantee of salvation.

Moral subdivision of the lower inferno

Passed the tomb of the Pope, because of the stench mentioned above, the two poets now have to stop, thinking that taking a pause can get them used to it (ewwww, it doesn't work with farts in the 21st century).

“It would be better to delay descent

so that our senses may grow somewhat used

to this foul stench; and then we can ignore it.”

So said my master, and I answered him:

“Do find some compensation, lest this time

be lost.” And he: “You see, I’ve thought of that.”

Line 10–15 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 11)

Dante asks Virgil to find a way to usefully spend the time, and the master begins to illustrate the moral topography of the lower Inferno (really? I would surely pull out my latest version of Monopoly:D).

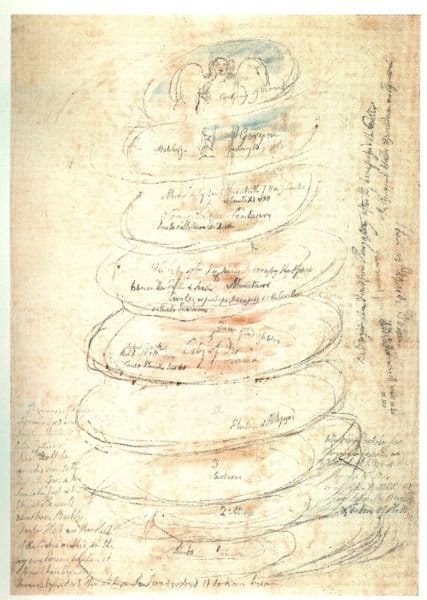

So you can already guess that this pause in the journey is just a narrative excuse used by Alighieri to introduce the readers to a sort of "map"

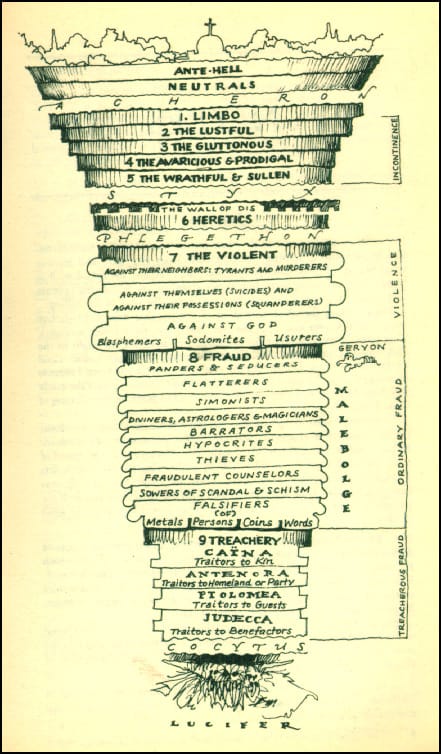

Virgil explains that beneath the city of Dis, there are three Circles, which punish the sins of malice.

Remember where we are? The city of Dis is in the 6th Circle (Heretics), so now we are looking at the 7th and beyond (Violent).

The purpose of malice is injury (insult or harm), which can be obtained with violence or fraud: and since fraud is more unpleasant to God, it is punished in the lower Circles.

The first of the three Circles (the VII), Virgil continues, houses the violent and is divided into three rings depending on who the target of the violence was, that is, one's neighbour, oneself and God.

- Those who are violent against their neighbour commit murder, wounding, robbery and arson: all of these are punished in the first circle. (God, wouldnt you want to rip apart your neighbours sometimes?)

- Those who are violent against themselves can be violent in their own person (suicides) or in their own goods (prodigals), and both are found in the second circle.

- Finally, one can be violent against God, in the divine person (blasphemers), in nature (sodomites) and in his goodness (in human industriousness, usurers) and all these are punished in the third circle.

Fraud, Virgil continues, can be committed against those who do not trust or against those who trust.

The first is less serious since it violates only the natural bond that binds men, therefore it is punished in the VIII Circle: here are found hypocrites, flatterers, fortune tellers, forgers, thieves, simonists, pimps and other similar sinners.

The second form of fraud is more serious, because it also violates the special bond that is created between people (kinship, homeland...) and is, therefore, betrayal: it is punished in the last and lowest Circle of Hell, the IX.

So yes, please do not commit fraud against those who trust you, it's not nice and also very unpolite.

Sins of immoderation

Dante says he is satisfied with the explanation, but has a doubt: why are the sinners he saw in the first Circles of Hell, namely the wrathful, the lustful, the gluttonous, the avaricious and the prodigal, not punished inside the city of Dis, given that God condemns them? And if it were not so, why would they be damned?

Virgil responds by reproaching Dante for not reflecting enough, and invites the disciple to rethink Aristotle's Ethics, where the ancient philosopher distinguishes the three dispositions:

Have you forgotten, then, the words with which

your Ethics treats of those three dispositions

that strike at Heaven’s will: incontinence

and malice and mad bestiality?

Line 79-82 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 11)

(if you wonder why I chose this picture is because Aristotle is represented here in the school of Athens holding a book of what? You guessed it, Ethics!)

incontinence (excess, not the urinary one), malice and mad bestiality. Incontinence is a less serious sin than the others and it is this guilt that the damned in the Circles pay for before the city of Dite, therefore it is perfectly logical that these sinners are punished differently from the violent and fraudulent.

Loan Sharks, what's their status?

Dante once again expresses his satisfaction with the clarified doubt and praises Virgil for his ability to heal every troubled view, but he still has an uncertainty that he begs the master to resolve.

Dante does not understand why money lending offends the divine goodness and Virgil explains that according to Aristotelian philosophy, nature takes its course from the divine intellect and its way of operating; as is clear in the book of Physics, human industriousness tries to imitate that of God, just as the disciple does with the master.

According to the book of Genesis, moreover, industriousness and work must provide the means of sustenance to man, while the usurer holds another path and despises nature and industriousness which is like his daughter, since he places his hope of gain in something else.

Having finished his explanation, Virgil invites Dante to continue his journey, since the constellation of Pisces has already appeared on the horizon (it is around four in the morning) and that of Ursa Major is to the North-West, in the area of the Chorus (the Mistral), while to descend into the Circle below there is still a certain distance to travel.

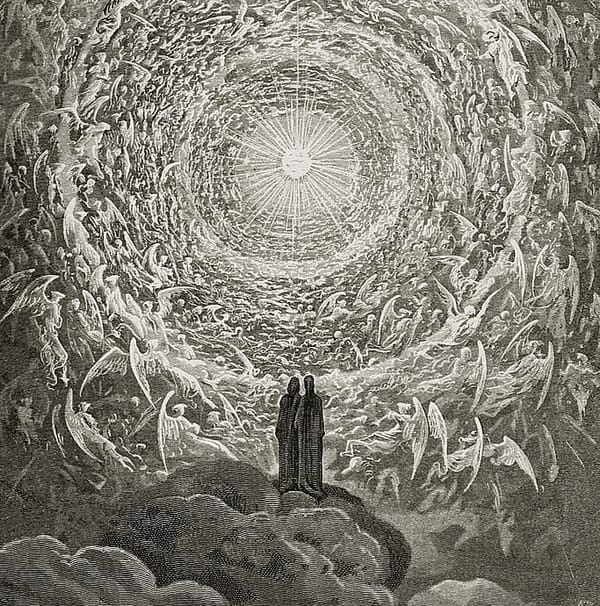

Reflections and conclusion

The function of this Canto is a bit "didactic-explanatory" (maybe even boring), but is needed, and more important than one might think.

It gives the infernal narrative (of which we are already participants) a measure and a rational order; this same order is a product of the wisdom that rules the universe, from the skies to the depths of hell.

However, what drew my attention in this canto, is the interpretation and discussion about usury.

This sin scarcely merits attention from the classical philosophers, but here it is Dante's main target of attack, alluding to the problems and social decline of Florence.

People who have been reading this course might probably understand that I'm not a religious person, but there is a great lesson here for us in the 21st century.

Those who live with money lending, instead of living directly with the given nature of the world, employ their "arts" - or their capacities for productive work - on the manmade resource of money, and thus break the link of love which, through our engagement with the natural world as a creation of God, joins us to the creative process of divine love.

Now, whether you believe in god or not, it is quite a strong point as our whole economy today is based on debt, with corporations making money with just other money sitting and doing nothing.

I hope you enjoyed this Canto 11 analysis, I’ve been reading during this cold but sunny October in Kent, UK - after finishing this massive puzzle Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights!

As usual, if you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact me via email or the comment section below.

Find some useful links and don’t forget to comment and subscribe!

P.S. After a long wait, canto XII is now released, click below to read!

Useful Links