Dante’s Inferno: Canto X

The heretics, Farinata and Cavalcante. Two Gentlemen meeting another pair of colleagues in the afterlife!

DIVINE COMEDY SERIES

The heretics, Farinata and Cavalcante. Two Gentlemen meeting another pair of colleagues in a recreational field: full of fire, souls and tombs!

Hello fellow readers, if you made it this far not only you had the patience of waiting for the slow release of this series, but also a love for what expects us in the afterlife!

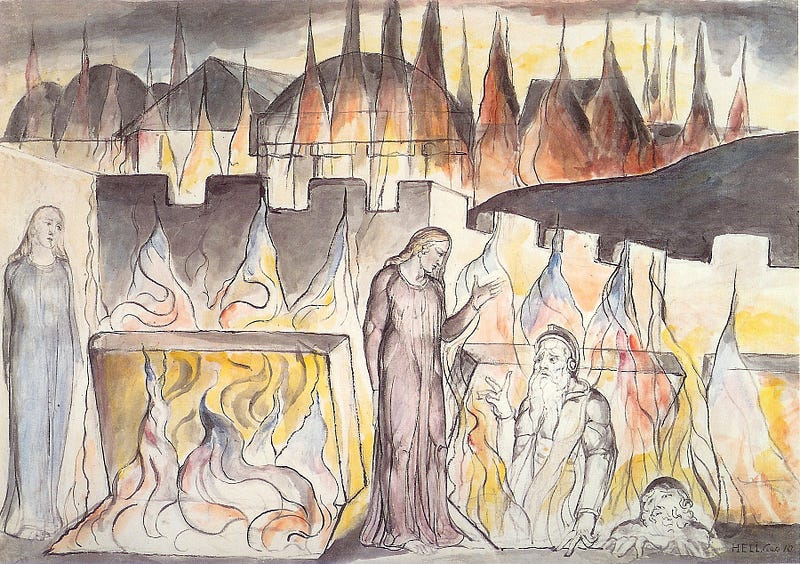

Welcome to the city of Dis, a wicked location in which from now the sinners are treated on a way different scale from the previous ones (by Christian standards).

Heresy? Please give me more 😈

The first sinners Dante encounters are the ones for heresy, entombed in fire with the lids of their sepulchres open (very nice).

By now, we know that Alighieri is always curious about his surroundings (who wouldn’t be?), so he asks Virgil what on earth (sorry for the pun) is going on.

‘You,’ I began, ‘true power and height of strength,

you bring me, turning, through these godless whirls.

Speak if this pleases you. Feed my desires.

Those people lying in the sepulchres -

What is there of seeing them? The lids

are off already. No one stands on guard.’

Line 4–9, Canto 10 (tr. Robin Kirkpatrick, Penguin Readers)

I have to admit, while that line “Feed my desires” does sound vaguely metrosexual, it does come from genuine curiosity :)

Strictly speaking, heresy is the result of obstinacy or confusion in the minds of Christian thinkers which leads them into contention with orthodox understanding.

Virgil replies that the tombs will be closed forever on the Last Judgment Day, when the resurrected souls will have reclaimed their bodies in the valley of Iosaphat.

He also explains that in this sort of cemetery lie all the followers of Epicurus, who proclaimed the mortality of the soul (meaning that when the body dies, so does the soul or “conscience”); then promises Dante that the desire he expressed to him and another that he did not reveal will soon be satisfied, namely to know if there is the soul of someone familiar.

Tuscans, always fighting each other

“O Tuscan, you who pass alive across

the fiery city with such seemly words,

be kind enough to stay your journey here.

Your accent makes it clear that you belong

among the natives of the noble city

I may have dealt with too vindictively.”

Line 22–27 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 10)

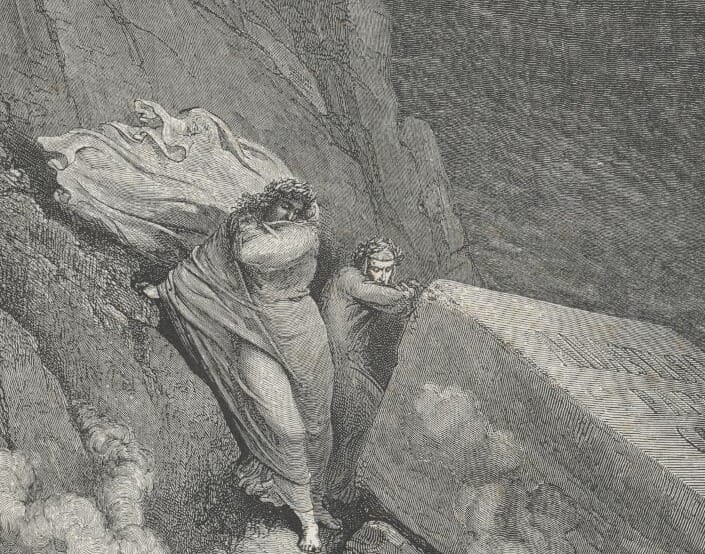

In case you are wondering who is coming up with those words, it’s the lovely gentleman coming up from a tomb in the illustration above, a Ghibelline warlord AKA Farinata Degli Uberti.

Guelph vs Ghibelline

To understand who this elegant gentleman is, we need to digress a little bit.

Between the 12th and the 13th century, the political life in Florence was polarized due to issues between two factions: Guelphs and Ghibellines.

A struggle had broken out between the Pope and the Emperor as both wanted to obtain maximum power over the city. Issues such as taxes, the nomination of bishops, abbots and daily administration were at the core of the political power struggle.

The Guelphs (Dante’s party) were those who supported the Pope, while the Ghibellines were those who supported the Emperor (Holy Roman Empire). Over time, these two factions tended to expand into other Italian cities, concluding their struggle with the expulsion of the Ghibellines in the fourteenth century.

As soon as Dante reaches the foot of Farinata’s tomb, he asks him who his ancestors were.

The poet reveals his lineage and Farinata observes that Dante’s ancestors were bitter enemies of him, of his ancestors and of his political party (the Ghibellines), so much so that he drove them out of Florence twice. Dante promptly replies that, if they were expelled, they were able to return to the city both times, while the same cannot be said of Farinata’s ancestors.

Alright chill guys, a bit of tension going on here!

All poets have a dad

Dante then notices that next to Farinata, someone else stands up on their knees:

“If it is your high intellect

that lets you journey here, through this blind prison,

where is my son? Why is he not with you?”

Line 58–60 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 10)

This is quite a big surprise as the person who just got up is the father of Guido Cavalcanti.

Guido is a great friend of Alighieri, probably his first true friend; to him he dedicated his first work called “La Vita Nova”.

The spirit looks around anxiously, looking for someone next to Dante who, however, he does not see. Finally, crying, he asks Dante where his son is and why he does not accompany the poet on this journey, if Dante is there because of the height of his genius.

I have to admit if I were a dad, I would ask the same question to a poet coming from the living onto my pitch!

Dante immediately understands that it is Cavalcante dei Cavalcanti, father of his friend Guido, and replies that in reality he is there not only for his merits; indicating Virgil as the one destined to guide him to someone who, perhaps, Cavalcante’s son had in disdain.

Cavalcante stands up alarmed and asks Dante if his son Guido is really dead: since the poet is slow to respond, the damned man falls back into the tomb never to return again.

Time, Powers and Sight

Farinata, not at all moved by what had happened, continues his speech with Dante, picking up exactly where they left off and says that if his ancestors were unable to return to Florence after the expulsion, this causes him more pain than infernal punishments; mentioning how this “art” (aka the exile) will be hard for Alighieri too ( giving a future prophecy).

Indeed, no more than four years will pass until Dante also knows how much it weighs not being able to return to his own city (see his exile here).

Shortsightedness? No, Presbyopia

Now if you are an attentive reader you might have noticed that the dead can foresee future events (Dante’s Exile), but they can’t see the present (the father of Guido Cavalcanti asking the question to Dante).

Farinata explains that the damned do see the future, but imperfectly, managing to see events only when they are very far away; when they are approaching in time or are happening they become invisible to them and they are unable to know anything about it, unless others bring them news.

Therefore at the end of time, after the Last Judgment, their knowledge of the future will be completely cancelled out.

People who have been following me for a while know that I used to be an optician, and I can't help myself give this little explanation!

Presbyopia — from Ancient Greek πρέσβυς (présbus, “old man”), and New Latin -ōpia (“vision problem”) = Can’t see close due to old age.

Shortsighted (AKA myopia) — from Ancient Greek μυωπία (muōpía, “shortsightedness”), from μύω (múō, “to shut, close”) = Can only see close, so far is a struggle.

Hard feelings, apologies and a bit of stink

Our poet now feels sorry, because he left Cavalcanti with anxiety regarding his son, so begs Farinata to tell him that his son is still alive and in the world of the living.

Then, as if penitent for my omission,

I said: “Will you now tell that fallen man

his son is still among the living ones;

and if, a while ago, I held my tongue

before his question, let him know it was

because I had in mind the doubt you’ve answered.”

Line 109–114 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 10)

Virgil calls Dante back, who therefore hurries to ask the damned man who he shares his pain with in the tomb.

Farinata replies that he lies there with more than a thousand souls (really? I thought it would be busier down there!), including those of Frederick II of Swabia and Cardinal Ottaviano degli Ubaldini, while he remains silent about the others. At that point Farinata returns to the tomb and Dante follows Virgil, sadly thinking back to the prophecy of exile.

After a while, the Roman poet asks Alighieri the reason for his confusion and the disciple reveals his worries. Virgil admonishes Dante to remember what he has heard against himself and promises him that when he arrives in Paradise, in front of Beatrice, she will provide him with every explanation relating to his future life. Then the Latin poet turns left and leaves the walls to take a path that leads to the external part of the Circle, from where an extremely unpleasant stench rises.

Conclusion

Hope you enjoyed this Canto X (10) analysis, I’ve been reading it after a pleasant day in good company at the British Museum (an Exhibition with Michelangelo’s original drawings after he turned 30 years of age).

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact me via email or the comment section below.

As usual, find some useful links below and don’t forget to comment and subscribe!

P.S. After a long wait, canto XI is now released, click below to read!

Useful Links