Dante’s Inferno: Canto VII

Divine Comedy Series- Summary of Inferno, Canto 7. Workout is a big deal in hell, and so is the lottery and religion! #Dante

DIVINE COMEDY SERIES

Workout is a big deal in hell, and so is the lottery and religion. If it weren’t for Plutus, you wouldn’t be able to discern Inferno from Earth!

Gibberish at its finest

Taking over from canto 6, we start this section with a unique exclamation:

“Pape Satan, Pape Satan aleppe!”

so Plutus, with his grating voice, began.

Line 1–2, Canto VII (tr. Barolini Teodolinda, Columbia University)

Plutus shouts this sentence that has been a question mark for a long time, and still, we have no certain idea of what that means (if you do, please leave a comment!).

(Confused about who Plutus is? See canto VI explanation here)

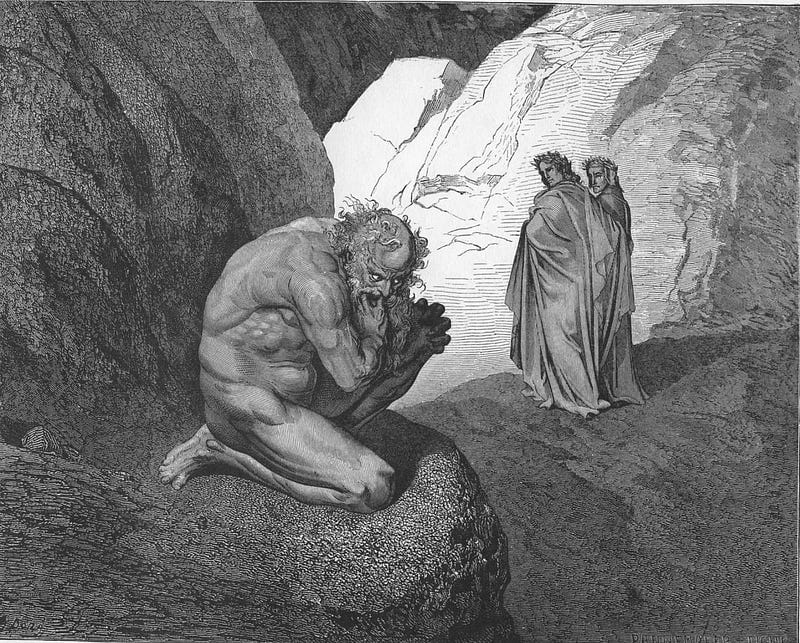

Virgil like with Charon (Canto 3), dismisses the odd god. The vermin watcher quiets down, letting the two poets pass by and enter the 4th circle of damned (Thanks Virgil, you always save the day).

Avarice and Prodigality

These sinners are misers who held onto their material goods excessively (avarice) and prodigals who spent their material goods inordinately. In Wordsworth’s words: “Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers” (The World Is Too Much With Us).

This is the only time we see 2 types of sinners put in such a way, as the opposites (other favourite translations for these sinners are Wasters and Hoarders).

It’s a clear message coming from ancient Western philosophy, the famous “In medio virtus stat”.

A Latin phrase reflecting the philosophy of Aristotle which means: “Virtue (or truth) stands in the middle.” In other words, truth is not to be found in either extreme of too much or too little.

Why is this important? Because here Dante sees the sinners, and thinks about them through an Aristotelian lens and not a Christian lens.

Through study, search, curiosity and good dose of common sense we can all overcome the limits imposed by being sons of our time; In Dante’s lifetime is Christianity, in our time is probably the pervasive political correctness.

Keep ’em rolling

Now that we know what these souls have in common, is time to find out what workout they are sentenced to!

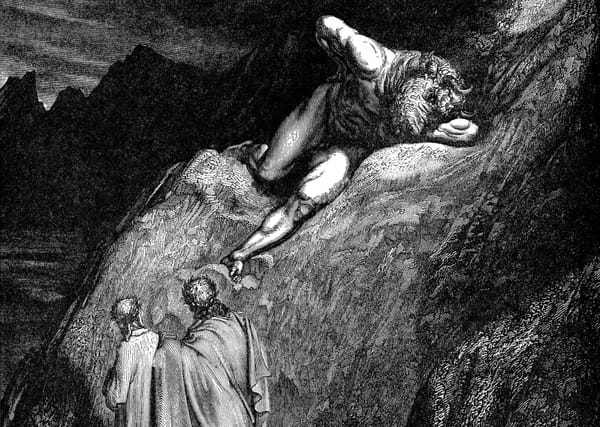

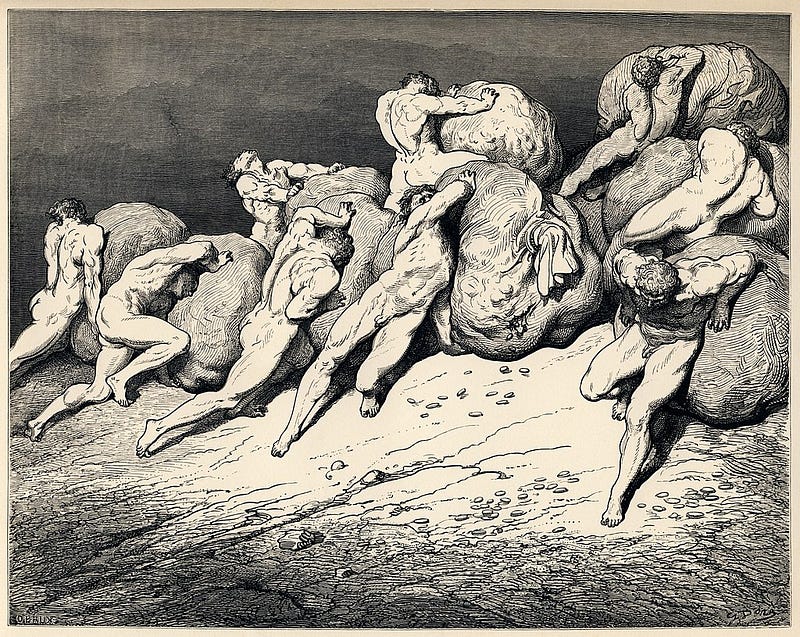

They are condemned to push boulders, divided in ranks proceeding along the circle in 2 separate directions.

When one hits the other the following happens:

They struck against each other; at that point,

each turned around and, wheeling back those weights,

cried out: “Why do you hoard?” “Why do you squander?”

Line 28–30, Canto VII (tr. Barolini Teodolinda, Columbia University)

So one rank pushes boulders and the other pulls them (ain’t that clever?); if you want to feel useless, this is exactly the place to be!

Clerics are not the innocents we think to be

Dante, seeing a multitude of souls fashioning a “Tonsure haircut” (yes, the silly one of the friars), asks his teacher if these are all people from the religious ordains.

To Alighieri’s eyes, seems impossible for so many people of religion to be here, but is a clear introduction to the topic of corruption in the clergy.

Virgil answers his question by mentioning that indeed these are clergymen, including popes, and there is no hope of recognizing who is who as their sins have corrupted even the way they look (how convenient!).

The one who clutches all world’s goods

Virgil concludes by saying that all world goods, entrusted to Fortune, are ephemeral and all the gold of this world would not be enough to quiet down these souls.

Where is my luck?

Dante is understandably confused and asks his master who is Fortune.

Virgil, being quite surprised, condemns Alighieri’s ignorance on this topic:

O unenlightened creatures,

how deep — the ignorance that hampers you!

I want you to digest my word on this.

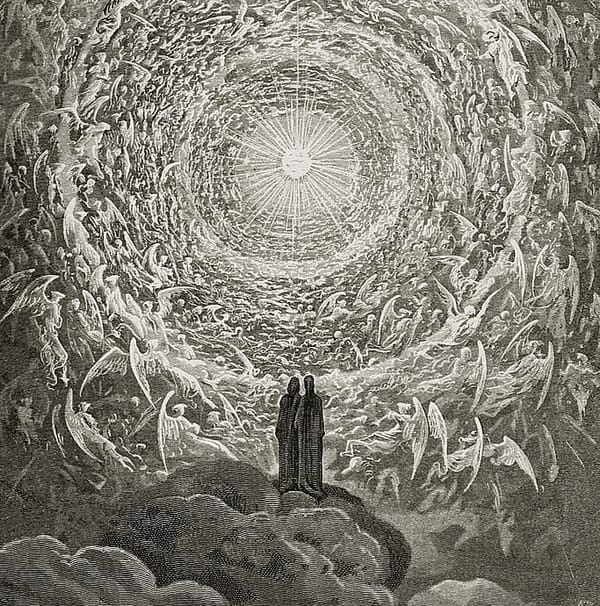

He explains that God appointed angelic intelligences to govern the various Heavens, and in the same way he created an intelligence to administer earthly goods.

Imagined as a female figure, Fortune, establishes when riches should change hands and which people should prosper or decline, according to the inscrutable divine judgment. Human wisdom cannot thwart its decisions and is inevitable that changes will be rapid.

Many fools curse her, when they should praise her and thank her: she does not even hear these complaints, she turns her wheel and works serenely together with the other angels.

(that is probably why I keep blaming my fortune on the lottery!)

At this point Virgil invites Dante to continue his journey, twelve hours have already passed since he left Limbo.

Styx: not the cool rock band, but an infernal river

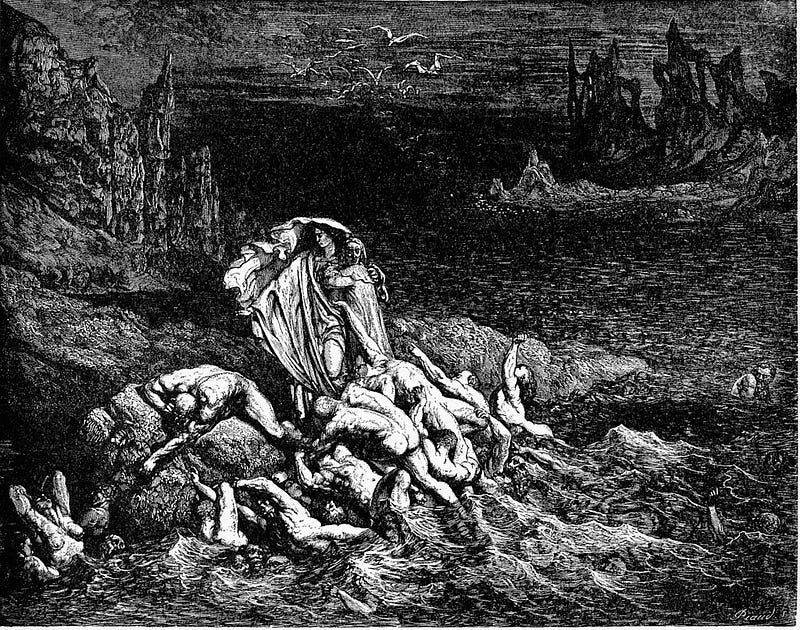

The two poets cross the Circle to the opposite end, where there is a vein of water that flows from the rock and flows into a moat. The water is dark in colour and the two poets follow its course downwards: the stream swamps the Styx, where souls are immersed in the mud which Dante observes carefully, seeing that they have a troubled appearance.

These damned people hit each other with slaps, punches and bites, even going so far as to tear each other to pieces (ouch!).

Virgil explains to Dante that these are the wrathful and there are other souls completely immersed in the Styx, who cannot be seen but sigh and make the water bubble on the surface: they are the worst of wrathful, bitter and difficult (sluggish/ Sullen), who repeat like a refrain a phrase that sums up their sin.

This canto ends with the two poets walking until they come at the base of a tower.

And so, on around this sour, revolting pit,

between the sludge and arid rock, we swung

our arc, eyes bent on those who gulped that slop.

We reached, in fine, the bottom of a tower.

Line 127–130, Canto VII (tr. Robin Kirkpatrick, Penguin Readers)

Comments from Antonello Mirone

This chapter, well known in Italy for its beginning sentence “Pape Satan, Pape satan aleppe!”, poses questions and exposes something that sticks with Italian society until today: incoherence and hypocrisy.

Dante does not recognize anyone from the clergy (quite convenient I say), even though he openly criticizes them; I believe it’s because he’s scared of any backlash. In that, he’s not far off modern legacy medias, or newspaper columnists.

We have already seen this in Canto III, where he addresses Celestine V not by his name, but by the one who made the “big refusal”.

What I’m glad about though, is the way he started observing the sinners in this section. All religious teachings are set aside for a short while, and a refreshing Aristotelian thinking comes in.

When we want, we can indeed move away from the mainstream thought of our time by updating it, and not utilizing it (in Alighieri’s case is the pervasive Catholicism).

Another thought threw me off in this read, and that is Fortune.

God appointing angelic intelligences to govern the various Heavens, and an intelligence to administer earthly goods?

If this does not sound pagan (even polytheistic), I don’t know what does! As much as Catholics (I am one by tradition but not belief) want to express how different they are from their pagan predecessors, the Christian world would not exist without ancient Roman, Greek and Mediterranean schools of thought.

The level of truth achieved by these civilizations has been so high, that even Christian philosophers could not ignore it and include part of it in the Catholic framework, and that includes even parts of pagan polytheism.

Fortune is a pagan god, that clergy managed somehow to fit into the mainstream religion at the time, making it pass as an “angel”. You will see modern priests wary of this and avoiding discussions on this topic, but the reason for this was only one: convenience.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this Canto 7 analysis, I’ve been reading over Christmas in the workshop while my father could not be bothered listening to my commentary (he’s not a good reader).

As usual, if you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact me via email or the comment section below.

Find some useful links below and don’t forget to clap, comment and subscribe!

What do Justin Timberlake and Canto 8 have in common? Read canto 8 here to find out more!

Useful Links