Dante’s Inferno: Canto III

Hell has a fancy entrance door, an ancient bearded doorman on a boat and lovely floors to explore.

THE DIVINE COMEDY SERIES

Dante’s Inferno: Canto III

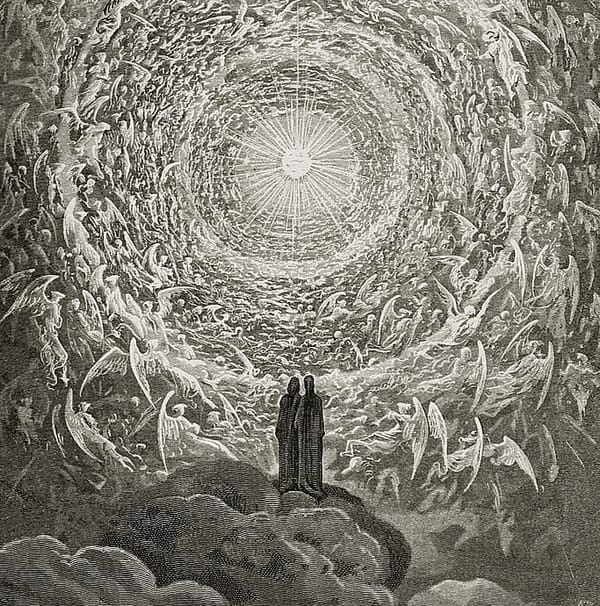

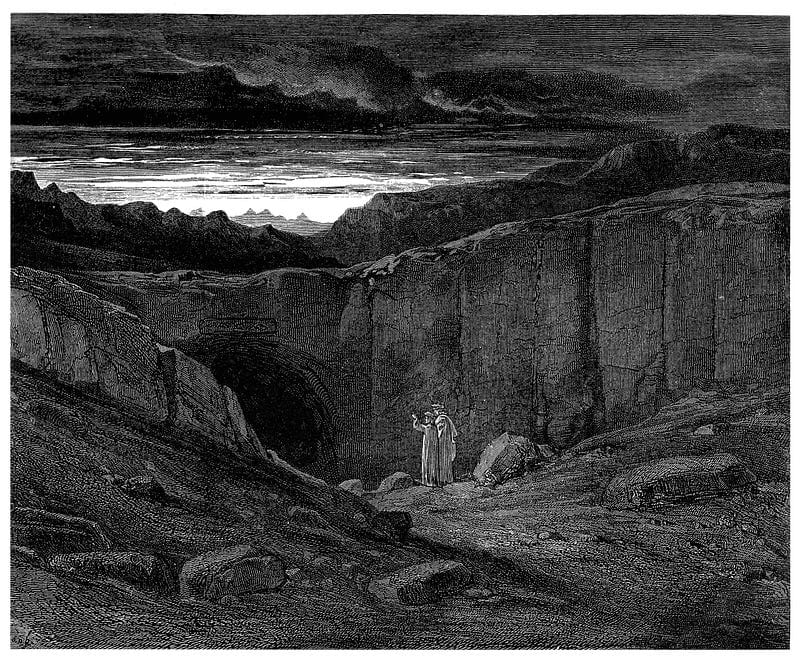

Here we are finally at the entrance of Hell, Dante wastes no time in narrative scene-setting to prepare the reader for the next strong words.

THROUGH ME THE WAY INTO THE SUFFERING CITY,

THROUGH ME THE WAY TO THE ETERNAL PAIN,

THROUGH ME THE WAY THAT RUNS AMONG THE LOST.

JUSTICE URGED ON MY HIGH ARTIFICER;

MY MAKER WAS DIVINE AUTHORITY,

THE HIGHEST WISDOM, AND THE PRIMAL LOVE.

BEFORE ME NOTHING BUT ETERNAL THINGS

WERE MADE, AND I ENDURE ETERNALLY.

ABANDON EVERY HOPE, WHO ENTER HERE.

line 1–9 (tr. Mandelbaum, Inferno: Canto 3)

These lines strike strong and they refer straight to not just Dante and Virgil, but ourselves, the readers.

All this terzina (tercet) expresses one idea — perenniality without escape from punishment.

Scared enough? Well, some people at this point might walk out (including me), but the two gentlemen are brave, and Virgil kindly reminds Alighieri to leave every doubt behind.

He reminds us that we came here to see the “miserable people,

those who have lost the good of the intellect’’.

At these words Dante cries, showing his attitude when placed in front of eternal pain, he expresses piety (or mercy) and it will accompany him in this chapter and the future ones.

Apathy belongs to hell

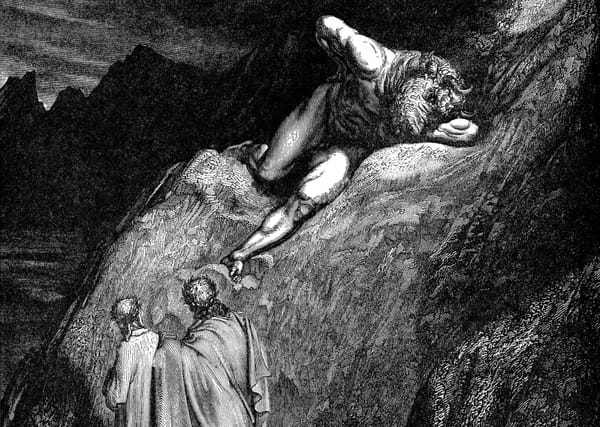

Both pass through the door, thus entering the underworld. The environment is dark, and weeping, lamentations and cries of the damned are immediately heard.

That antechamber of hell welcomes the apathetic:

those who lived without ever taking a position,

neither good nor bad, useless to themselves and to society.

These are unlike almost all other sinners in Hell in being unnamed. It is a mark of particular contempt for their wasted lives, to the point that names should be denied to them (that’s harsh).

The apathetic lament their fate, because they are neglected by all with contempt for not having left any memory of themselves alive.

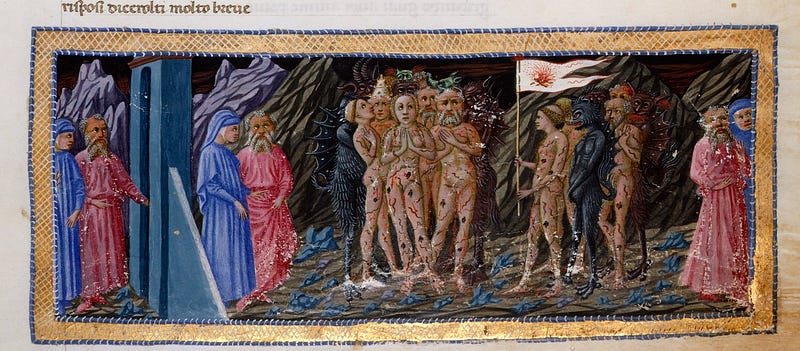

The punishment of the slothful is humiliating and contemptible: they are continuously stung by blowflies and wasps, in a putrid mud, so as to shed now in vain (they are only food for worms) those tears and that blood which they were unable to shed in life. They are also forced to chase after a flag that rapidly changes position at all times.

Do we have a VIP guest in this section?

Of course we do, Dante sees a figure that now is generally accepted as Celestine V, the one who out of cowardice had given up the papal office, giving way to Boniface VIII, whom the poet holds responsible for the evil of Florence and his exile (ouch!).

Celestine V’s resignation from the papacy had raised quite a lot of eyebrows in Christianity, and great regret in those who had hoped for a spiritual reform of the Church; the popular protests were also numerous to induce him to desist from that idea, it was discussed if it was even legitimate such choice.

So Dante, since the slothful has no name, with these words describes him.

I saw and recognized the shade of him

who made, through cowardice, the great refusal.

A river, a boatman and a loooong queue

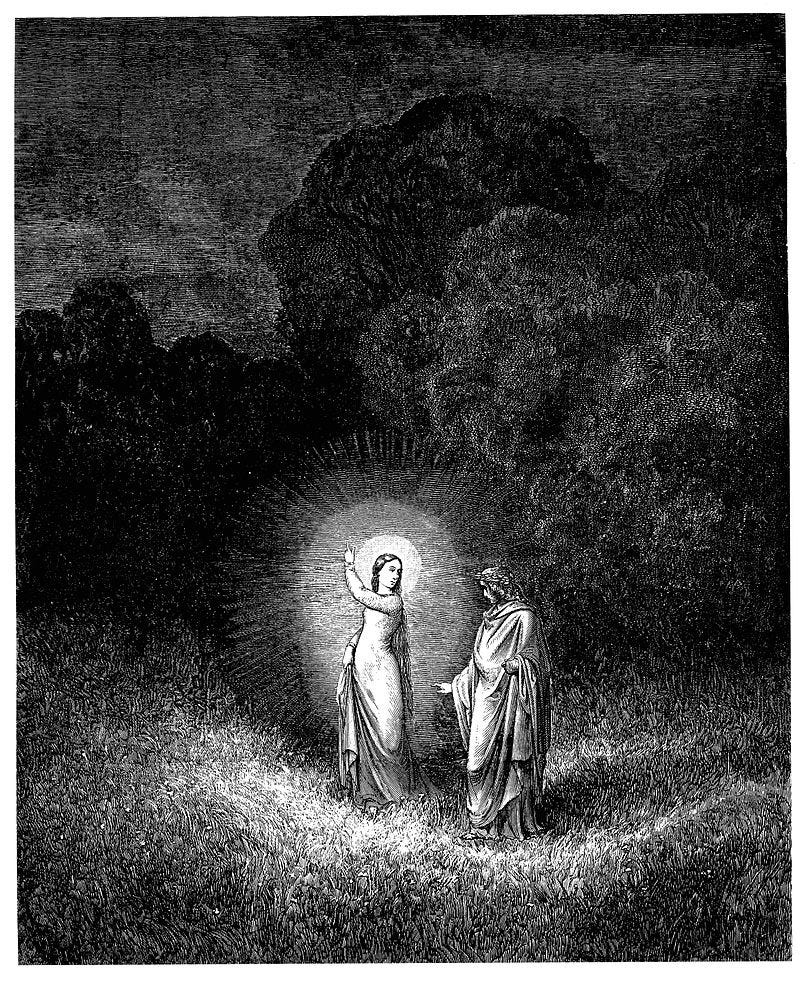

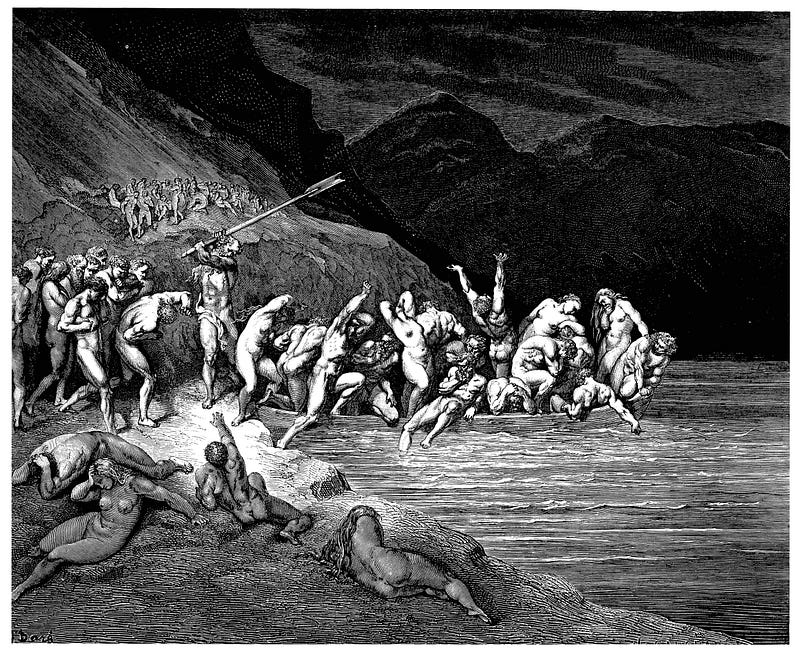

Continuing on their journey, the two poets arrive on the bank of the Acheron river where an immense group of souls is ready to be ferried to the other bank by Charon.

This is a figure directly from Virgil’s own account of the underworld in book 6 of the Aeneid. But the melancholic sublimity of Virgil’s description is here transformed into a highly visual depiction of demented power.

And here, advancing toward us, in a boat,

an aged man — his hair was white with years —

was shouting: “Woe to you, corrupted souls!’’

line 82–84, Canto 3 (tr. Allen Mandelbaum)

The helmsman carries out his task without wasting time: he orders the souls to get on the boat by making signs to them, and, if someone shows that he wants to linger, he beats it with the oar.

Charon, realizing that Dante is still alive, admonishes him to retrace his steps, and to wait for another boat made of “lighter wood”, normally reserved for souls going to Purgatory or Paradise.

Hearing this, Virgil forces him to silence revealing to him that his disciple’s journey is accomplished by the will of heaven, thus speaking:

‘Charon’ , my leader, ‘don’t torment yourself.

For this is willed where all is possible

that is willed there. And so demand no more.’

Line 94, Canto III (tr. Robin Kirkpatrick, Penguin Readers)

How can you not agree with a gentleman so well-spoken?

Charon, whose eyes were ringed about with wheels of flame, agrees to take them on.

The damned, meanwhile, blaspheme everything and everyone: from their lineage to their birthplace, to God.

Suddenly the earth trembles, and, while a flash of red light pierces the darkness, Dante loses consciousness (a convenient trick to change the scene!).

Hope you enjoyed this Canto III descriptive analysis, I’ve been reading it in the lovely city of Canterbury while walking through the fields.

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact me via email or the comment section below.

As usual, find some useful links below and don’t forget to clap, comment and subscribe!

Feelf reading to meet some VIPs? Read on Canto IV here.